Posted by Matt Bingham on Apr 10, 2014

In my “Welcome” note (see top Nav bar) I mention that students at Milton Academy will be contributing content to the site and blog. The following interview was conducted, and written up, by Jonathan Chan, Class III.

Jonathan is interviewing Robin Abbott who is the Greenland Science Project Manager for Polar Field Services. Polar Field Services handles all the logistics for National Science Foundation funded projects in Greenland.

1) How do the researchers get themselves and their equipment from the US to Greenland?

There are different ways to do this. The National Science Foundation has a contract with the 109th Air National Guard and they have a base in northern New York and often researchers will fly on the 109th. They put out a schedule at the beginning of the season and they usually fly starting in April and finish in August, and they usually fly for a week or so to Greenland and researchers try to use those flights to do their work and then come home. It’s sometimes tricky because everyone has their own time frame and sometimes their flights don’t work. So if that happens the researchers will use the Air National Guard plane for one way and then they will come back using commercial airlines. And how you get out of Greenland is from Kangerlussuaq to Copenhagen, Denmark. And then Copenhagen, Denmark you have to spend the night and then you fly out the next day and fly back to the United States. That’s why everyone likes to go on the 109th Air National Guard because it’s about a 6 hour flight and you get in the back of a C-130 or C-17 airplane and you fly to Kangerlussuaq, Greenland and you’re there. So there is no change in airplane and having to get in hotels and things like that. These aircraft also work in Antarctica so they go down there in our winter because its summer there and then they come and work for the Greenland side of things in the summer. Air Iceland is another way to get to Greenland but those are flights that mostly go to the east coast of Greenland but where we have an office is on the west coast of Greenland in Kangerlussuaq.

2) How do the researchers get to field sites once in Greenland and who owns or manages the transportation?

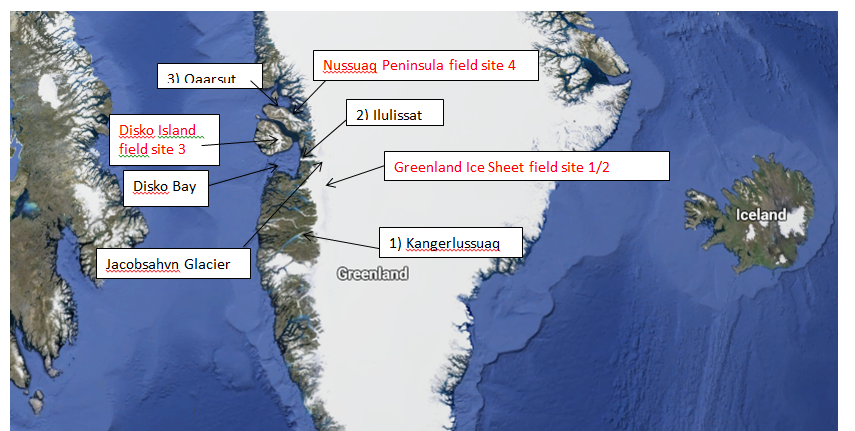

Sarah Das (PI on our project) for instance, needs to have both a Twin Otter airplane and a helicopter and so do some of their research, depending on where they go in Greenland. For example if you are in the snow up on the ice with big old ice caps they use a Twin Otter to get there. A Twin Otter is a fixed wing aircraft with two engines that seat about 10 passengers with the cargo and it has skis on it, so it goes up and lands on the ice cap and people can do their work there. Along the coast of Greenland it is very rugged and very mountainous so you have to use a helicopter to get to those sites because there is no landing area such as a strip or runway. If the cargo doesn’t fit in the helicopter they have to make a sling-load. They usually don’t like to put any people inside the helicopter when that happens but they like to put things inside. Sometimes with the smaller helicopters you need to sling-load. So with Sarah Das and her project, we just found out that her big long ice box will fit inside of the helicopter so we are happy about that just because its quicker.

3) Where do scientists stay/live while in Greenland?

When they fly to Kangerlussuaq on those C-17s or C130s, we have an office building there that is kind of like a dormitory and they have kitchens , bathrooms down the hall and everybody has to share a room. That’s where they will stay the first night. And if they are travelling, in the case of Sarah, the Twin Otter will pick them up the next day to fly up to the next town and to the ice cap. And at that time I have rented hotel rooms for them [in Ilulisaat]. Sarah has 6 people in her group so I have 4 rooms and some have to share but it’s a nice area for researchers to talk and work on their gear and things. And then the group has to go to another site which is a little too far to get back to Ilulisaat so they will stay in a town on an island north of Ilulisaat, and there they don’t have any hotels so I have talked to the airport manager who has some rooms for pilots and different people who need housing so I’ve rented those rooms for that Sarah Das project. So you just have to kind of find out where they’re going and see what resources are there. It is sometimes challenging because there aren’t hotels and motels everywhere in Greenland. It’s a very big country but it only has 58 thousand people in the country and they call it the biggest island in the world. Sometimes other researchers will camp out on the ice caps and there they might take tents and sleeping bags and camp out for a week or two.

4) Do scientists stay in Greenland year round like at the South Pole or McMurdo Station in Antarctica?

There are – these are the people working up at Summit Camp. This is a camp up on the Greenland ice sheet. It is in the middle of Greenland where they are studying snow chemistry and meteorology. They also do drilling of ice cores to look back at snow from years ago. They’ve got internet up there, a big old satellite dish and there are 5 people that stay there all winter long and monitor 30 some measurements. So the researchers go up there and set them up and we have people there that are called technicians and they will take readings all winter. There is mechanic there to make sure the generator is working to keep them warm and a manager too. They have beautiful Auroras this time of year (northern lights).

5) What safety training and or equipment do you or your company issue to the scientists?

We do ask that all scientists bring their own sleeping bags and their own clothes. We hope everyone is very smart and knows how to dress and we find that most people do and Sarah Das is extremely professional at this – she’s been doing this for years. But as far as equipment is concerned, where they are flying on a helicopter or a Twin Otter, we give them survival bags – basically 3 days of food (dehydrated meals), a stove, tents , sleeping bags – and all the things you would need if you got stuck out there and needed to survive and stay warm, but hopefully people don’t get in that situation. We also try to encourage people to go to field training of some kind. I think Sarah just had a class on glacier training for people going on her group. So we just encourage people to get some training on just how to walk on the snow, what to avoid if you’re going to be near crevasses; just all the risks that you might come in contact with out there. We offer these things and luckily Sarah did that. We have lots of things on our website you can read and there are different ways for people to get information to become quite savvy and smart when you’re out there in the wilderness.

6) No matter how well you set things up ahead of time there must be changes in plans due to weather, equipment, etc. How much of that do you have to handle on the fly while the field research is going on?

You’re right about that. Usually we try to bring backup equipment. Sarah’s got an extra drill she’s bringing just in case her primary drill isn’t working, and then handling things on the fly. There is nothing you can do about the weather so we work with Air Greenland for the helicopters and we work with Nordland Air which is from Iceland for our Twin Otters. We always work with the pilot and just try to figure out the plan based on the weather. Sometimes we need them to open the airports because in Greenland the airports close. They are only open from 8 to 5 and some of them are only open from 9 to 4 because there is just not much traffic going on there. Hard to imagine. Some airports they have to use helicopters and they are called heli-ports because they can’t land the airplanes. But anyway we just try to work with the provider, Air Greenland or Nordland Air, to figure out how can we get the work done and when we can do it and it usually works out pretty well – sometimes they have to send another helicopter because the helicopter is booked for someone else – so it’s a puzzle and that’s one of the challenges doing logistics – you make the best plan ever and it never goes just as you think it is going to. You love it when it works. You just try to do whatever you can do to get that work done for the scientists.

7) What are a major concerns/ obstacles in terms of transporting the ice cores back to the researchers’ labs in the US?

I think our biggest concern there is mostly in Greenland because we have to use freezers there that we are borrowing so we find out what the temp is going to be and what our access will be. As I mentioned the airport is closed sometimes so that makes it hard for the person who can open the freezer who has gone home so we have a person that works in Greenland for us and she travels around and tries to pave the way, make arrangements and get to know the people, the locals, and maybe they will give her a key or something so maybe she can get in after hours. But it’s always a concern-the freezers in Greenland-because mostly they don’t know whether and ice core box will fit in their freezer. So I found freezers in both these towns and they should do fine but then when it’s time to bring the samples back we kind of have to trust that they know the ice boxes should not be taken out of the freezers and sit there with their airplanes – you need to treat the ice boxes like frozen samples – like ice cream and get it on that plane and make sure it gets to the next site because some of these planes have two stops before they get to our freezer so you know each time there is a risk – what if the airplane breaks down etc.? You just kind of keep tabs on it the best you can. Once things get to Kangerlussuaq though, we have a freezer we can use there. We can turn it way down so it gets very cold and then we have what we call a “cold deck” on the C130s where there are no people on the deck and we’ll ask them to turn off all the heat in the back because we have frozen sample ice cores coming out . So they will fly that plane back to New York and at that end we have a freezer truck that we’ve hired and they will get the boxes off and deliver the boxes to the different universities.

8) Is there anything else interesting (tools, equipment, accommodation) that you could share?

I’ll tell you one thing. On the east coast of Greenland it is mostly accessed from Iceland and on the west Coast it is mostly accessed by Denmark. When you’re in Greenland, it feels like you’re in the past because there are a lot of hunters and they are selling meat and their fish is hanging and drying like you witness from way back and people are just very traditional. There is also a lot of Danish influence there and its very interesting and colorful – all the houses are really bright and they are still doing things like going out on sleds and hunting polar bears and walruses and all these things up north.

(This interview transcript has been edited (minimally) from Robin’s actual language for clarity).

Read More

ore on Tuesday’s planning at the end of the day.

ore on Tuesday’s planning at the end of the day.

FOLLOW US ON TWITTER

FOLLOW US ON TWITTER